With a slow start to the year, most restorers are reporting lower than normal workloads and poor cash flow. Some are right-sizing operations to ride out the turbulence while others are ramping up to prepare for the kind of storm that creates work for our industry. Being almost two years removed from the last major landfalling hurricane in the United States (Ian 2022), we can only imagine how that pent up enthusiasm will play out when the next one arrives.

Around this time each year, we are reminded of climatologists’ predictions of a more active storm season with a greater frequency and intensity of events. Some will say it’s because of El Nino, and others will credit La Nina. Personally, I’m a numbers guy, and what history reveals is that there have only been 12 years in the past 50 when we didn’t have a landfalling hurricane in the U.S. Furthermore, there have only been three times during this same period when we had back-to-back years without one. This means we have a 94% chance this year of seeing a storm that will be large enough to create work somewhere in the U.S. Get ready folks—work is on the way!

Unfortunately, planning is not a discipline that comes naturally to many contractors in the restoration industry. Most of the work in this business is unpredictable and inconvenient. More often than not it comes in waves. Productivity is only limited by a contractor’s ability to generate leads and their capacity to perform the work. With CAT work, leads are abundant and securing work is generally not hard to do. Securing the right kind of work is perhaps the greatest issue, but that’s a topic for another day.

Assuming your company has the right kind of work figured out, let’s set our sights on maximizing productivity from CAT events through planning and preparation. In my personal experience in the early 2000s and through coaching our clients over the past 15 years, making the most of these opportunities involves focused planning in four essential elements: Logistics, Resources, Communications, and Risk Management. Let’s explore each of these and the critical roles they play in producing results with more efficiency and profitability.

1. Logistics

It’s been said that timing is everything in business, and responding to a CAT event is no different. Arrive too soon, and you risk wasting precious time and money while you sit idle, waiting for things to develop. Arrive too late and you risk missing the window of opportunity to secure work before it gets gobbled up by the competition.

Seasoned restorers who routinely travel for CAT work will hedge their bets on a storm by staging resources within a 6- to 8-hour drive of the area that is predicted to be ground zero. However, this is not as easy as it might seem. Hotel accommodations can be limited by high demand from competitors, insurance companies, and utility workers all heading to the same areas. Couple this with evacuees fleeing in the other direction, and you can imagine the challenge.

The best solution to this issue is to negotiate hotel contracts well in advance of being needed. If you can get a hotel chain or an ownership group to commit to a rate and priority of availability based on a percentage of occupancy at the property, you will be way ahead of the game when the time comes. The holy grail of deals would be for your company to be named as the contractor of record if their property is damaged by a storm. You just need to be reciprocal with your pricing and benefits so there is equal value to both parties.

Pulling this together in real time, along with other logistical scenarios like transportation, requires a large commitment of a planner’s time and a healthy dose of patience. Often, this is done months, if not years, in advance. It involves multiple scenario analyses of potential events that could impact various geographic regions where a response would most likely be needed.

My preference was always to identify potential staging areas first. Lock down some agreements in primary and secondary locations, then work the transportation and deployment strategies around them, keeping in mind the major highways and other options for travel that could put the teams inside of that 6- to 8-hour radius of potential work.

2. Resources

Planning for the labor, supplies, and equipment needed to perform a large amount of work in an unfamiliar location means establishing a LOT of relationships. This is best done when things are quiet—at trade shows and industry events—when suppliers have the time to rationally work through the terms of potential partnerships without the noise and distractions of an impending storm.

When restorers think of resources, everyone immediately thinks of drying equipment and consumables. While these are important, they are by no means the least available. Most suppliers will respond in mass with these items, so scarcity is not an issue.

I would encourage contractors to focus first and foremost on generators and fuel. Most badly damaged areas will go weeks without electricity, and without electricity, there isn’t much work that gets done. When negotiating agreements in advance for these items, you should expect to pay hefty retainers for the most reliable service. Remember, the biggest competitors for these items are not other contractors. They are retailers in the local markets looking to reopen their stores as quickly as possible.

Labor resources can be tricky and largely unreliable to procure, tempting many to truck crews from their home states. I would advise against this strategy because the greatest deficit in this scenario is limiting capacity in local service territories and ruining the reputation of those who produce normal revenue streams. Instead, I would recommend finding five to ten reputable labor services that broker crews as a business. Most of these folks know the game and are open to negotiating rates and terms on an as-needed basis. Just make sure that U.S. employment eligibility and payroll taxes are verifiable, and that non-English speaking crews have bilingual supervisors.

3. Communications

With technology providing the luxury of constant communication, the ability to communicate is rarely an issue in CAT scenarios. I can only remember one event in recent years when satellite phones were needed. What does create issues is the quality of communication stemming from what information needs to be communicated between the right people at the right times.

Planning for effective communication during CAT work begins by establishing a virtual organizational chart that clearly shows a chain of command, lines of communication, roles, and responsibilities. In this scenario, typical reporting structures might look different than they do in everyday business. I recommend breaking down the chart into the critical areas of responsibility, including business development, procurement, project management, and administration. Everyone stays in their lane, and communication between these areas occurs at the top, while they all report to a senior manager who plays quarterback.

Once the team structure is organized, then a communication planner can be established and distributed to all parties for reference. This document should clearly outline the following:

- Audience – the required recipients of the information

- Output – the information that is being communicated

- Timing – when the information will be communicated

- Delivery – how the information will be communicated

- Lead – the person responsible for communicating the information

The communication planner serves as the bible for the CAT team and should be followed without exception. Couple this with a schedule of standing daily meetings between the team members, and you’ll have a bulletproof plan for effective communication for CAT response. It will streamline operations and reduce common scenarios that can lead to costly mistakes.

If you would like a copy of this communication planner and other valuable project tools, sign up for a free trial of V Street at: https://violand.com/vstreet.

4. Risk Management

Speaking of mistakes, our last element of CAT planning is an essential part of minimizing failures that are common to even the most seasoned restorers. While most of the risk associated with CAT work—such as payment, health and safety, environmental, and regulatory compliance—is known, there can be many unknown risks which seem to come out of left field and derail projects quickly. This makes risk management even more important.

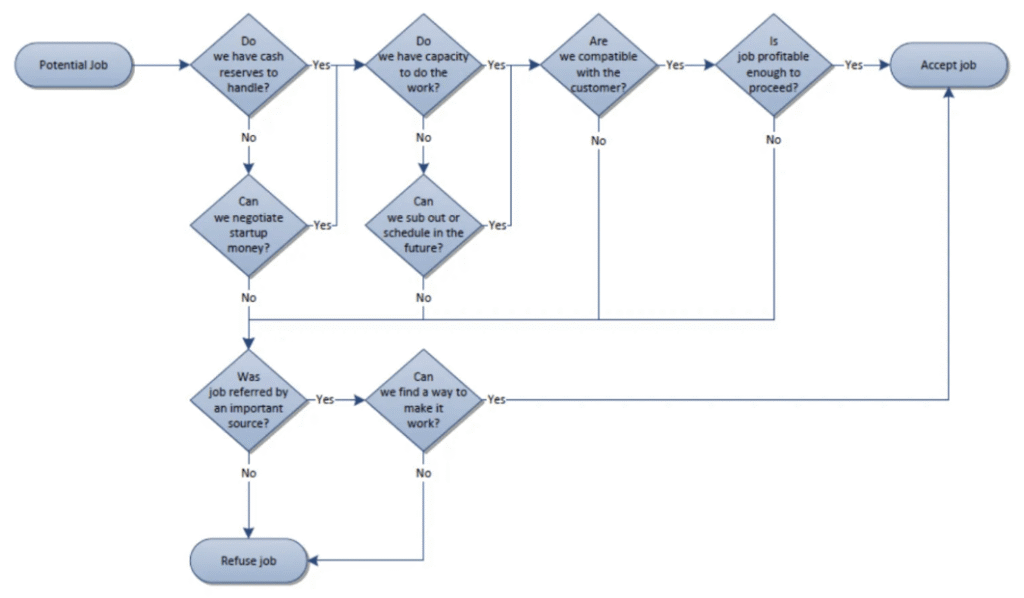

While not all scenarios can be planned for, it is of the utmost importance for the showstoppers (high probability, high impact) to be addressed with a plan to avoid them or to mitigate their impact if they do occur. For this reason, I advise clients to consider using a decision tree to outline the conditions that warrant stopping a process. This involves asking a series of yes or no questions. If the scenario survives the series and a planned way forward can be established, it’s a go. If not, contractors need to be respectful of the process and disciplined enough to say NO before learning a lesson the expensive way.

Above is an example of what this might look like for deciding whether or not to pursue a project opportunity.

Plan Relentlessly and Execute Flawlessly

Several years ago, I was honored to address a group of restorers on a piece I wrote about catastrophe work titled The Great Gamble. The central theme of the presentation and article was how to make a calculated business decision about pursuing CAT work. Every time a weather system starts spinning in the Caribbean, I receive many calls and emails from eager contractors looking for my opinion about this very decision. My response is always the same, “Don’t go to the party if you’re not invited.”

If you’re looking for an invitation, you must plan for it. If you get the invitation, then you’re going to need the logistics, resources, communications, and risk management to be successful…and you must plan for it. There is a direct and proven correlation between these elements. By incorporating them into your catastrophe response planning, you can improve efficiency, reduce costs, and, ultimately, increase profitability with these services.

Published in C&R Magazine